Tonight's sunset at La Renaudière. It's cold but it's been sunny for a couple of days now. They're saying it might snow some tomorrow afternoon. We are ready for springtime weather.

Tonight's sunset at La Renaudière. It's cold but it's been sunny for a couple of days now. They're saying it might snow some tomorrow afternoon. We are ready for springtime weather.

11 February 2006

Sunset tonight

Tonight's sunset at La Renaudière. It's cold but it's been sunny for a couple of days now. They're saying it might snow some tomorrow afternoon. We are ready for springtime weather.

Tonight's sunset at La Renaudière. It's cold but it's been sunny for a couple of days now. They're saying it might snow some tomorrow afternoon. We are ready for springtime weather.

09 February 2006

It all starts to blur

If you want to read this series of postings in chronological order, start here: Quitting California. It's the story of leaving California and buying a house in France. Click Next at the bottom of each article to jump to the next one in the series.

On Wednesday morning we saw four more houses. Here’s what I remember.

One house, near Montrichard, had a little swimming pool. That wasn’t anything we particularly wanted (though a hot tub might be nice). A pool seems like a maintenance headache, and this one wasn’t very attractive. It was too small, to start with. The house itself had a lot of small rooms off a long hallway. It was right on a road, and crowded by other houses. Crowded was the way the whole place felt. Let's keep going.

Another house in Montrichard was completely without character. It was fairly big and completely empty. It was carpeted throughout in beige, and the walls were beige. The front yard, or what passed for one, was a large plot of gray gravel. The exterior walls were beige. There was a little yard/garden on one side. The environnement was dull. We took a pass.

A house in the village called Bourré, near Montrichard, was one of the nicer ones we saw. It was modern and well maintained. There was a mother-in-law apartment downstairs, with lots of built-in furniture and wood paneling, all in knotty pine. The man selling the place -- he and his wife were moving back to Brittany, where they had come from -- was very proud to show us the electric front-gate opener he had recently had installed. He played with that little genie remote control unit the whole time we were there, showing us how the gate would open and close at the touch of a button. He must have thought we had never seen such a thing, but our the garages in every house and apartment building we lived in in California had them. The back yard of his house in Bourré was huge but went straight down a steep hill. The nextdoor neighbor’s yard was a construction zone -- piles of concrete blocks, bricks, and other building materials were everywhere. His house appeared to be about half finished. We moved on.

Back in Montrichard, along the river banks, we saw what might have been the nicest and best-maintained house we saw all week. The subject of flooding came up, since the house’s back yard ran down to the riverbank. We went downstairs into the garage and basement, where the owners had had a nice guest bedroom/bathroom suite put in. They pointed out to us that the water had only been about two feet deep in that room and in the garage during the flood two years previous. This house was down and across the street from one we had seen on Monday, and the gypsy encampment was still down at the end. Too bad about all that, because it was a very nice house. It was listed at a price over our stated budget, but Bourdais thought they might accept an offer at the lower price, if we made one. They were ready to move on. So were we.

Back in Montrichard, along the river banks, we saw what might have been the nicest and best-maintained house we saw all week. The subject of flooding came up, since the house’s back yard ran down to the riverbank. We went downstairs into the garage and basement, where the owners had had a nice guest bedroom/bathroom suite put in. They pointed out to us that the water had only been about two feet deep in that room and in the garage during the flood two years previous. This house was down and across the street from one we had seen on Monday, and the gypsy encampment was still down at the end. Too bad about all that, because it was a very nice house. It was listed at a price over our stated budget, but Bourdais thought they might accept an offer at the lower price, if we made one. They were ready to move on. So were we.Finally, we saw a house in the town of Pontlevoy, just 5 miles or so north of Montrichard. It was owned by an older couple who were there to take us on a tour. It was very old-fashioned and needed a lot of updating. There was a lot of unfinished space that the man used for various workshops. The garden was not huge but was beautifully planted with espaliered apple and pear trees. Unhappily, there was a big warehouse of some kind right across the street. Again the setting wasn’t what we were looking for. Au revoir.

That was Wednesday morning. At noontime, Bourdais asked us if we would like to see some houses in Amboise, which had been our original idea, that afternoon. We said yes, of course. He told us to go to his office in Amboise at 2:30. One of his agents there would show us three houses in our price range. That’s what we did.

One house was brand new. It was on a small lot in a suburban development. You got the impression that it was sitting in somebody else’s front yard, since there was another house facing it from behind, and there was no privacy whatsoever.

The second house was enormous and fairly new. It had a huge living room with very high ceilings and a big mezzanine. There were four big bedrooms, and the kitchen was very nice. But there was no land whatsoever. The driveway was an easement on another property, and there was no garage.

The third house was smaller and darker. On the top floor, it had two studio apartments that the owners rented out to students from a language school nearby. We couldn’t see ourselves living there with renters overhead, and again, there was absolutely no land. The dog wouldn't like it.

The third house was smaller and darker. On the top floor, it had two studio apartments that the owners rented out to students from a language school nearby. We couldn’t see ourselves living there with renters overhead, and again, there was absolutely no land. The dog wouldn't like it.We had asked Bourdais if we could go back to la Renaudière Thursday afternoon and spend a couple of hours there looking at the place and taking pictures. He agreed. I think he knew we had made up our minds.

Next: Where do we sign?

08 February 2006

Seven-hour leg of lamb

This method of cooking a leg of lamb keeps catching my attention. A few weeks ago, I saw a chef on the French Cuisine TV demonstrate his method for preparing what in French is called un gigot de sept heures. Then one morning last week I heard food expert Jean-Pierre Coffe talk about it on a France Inter radio show.

I'm making it today. I had a gigot from one of our friend Gisèle's lambs in the freezer. No, this time I don't know what the lamb's name was. She usually does give us that piece of information, but neglected to this time. I didn't ask.

Here's how it's done. You brown the leg of lamb on all sides -- I browned it under the broiler. The recipe I have printed out calls for including a pied de veau, but I didn't find one of those yesterday at the Atac supermarket in Amboise, so I bought a pied de porc instead and am using that. I put it in the pan with the gigot to brown under the broiler. I hope the pig's foot produces a good amount of gelatin as it cooks, to enrich the sauce. I think it will.

Somebody asked me if I knew what the pig's name was. Ha ha ha.

While the meat is browning, you chop some carrots and celery and cook them in a wok or sauteuse with a couple of small onions, seven or eight shallots, and seven or eight garlic cloves, all peeled but left whole. Add a couple of tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped (or not seeded if you don't want to -- I didn't). When the vegetables are starting to brown, deglaze the pan with a quart of veal broth if you have it -- I used turkey broth because that's what I had in the freezer. Chicken or vegetable broth would be good too.

When the gigot was browned a little, I poured the vegetables and stock over it in the pan and added some thyme, peppercorns, allspice berries, and bay leaves. I added another quart of broth so that the leg of lamb is sitting in a couple of inches of liquid. Then I covered the pan and put it in the oven.

Jean-Pierre Coffe and my Cuisine TV recipe both call for cooking the lamb for four to five hours in a slow oven (110ºC / 225ºF). Why do you call it a gigot de sept heures if you only cook it for five hours? the radio interviewer asked Coffe. Well, in the olden days it cooked on the edge of the stove or fireplace, where the temperature couldn't be regulated very precisely, Coffe said. It took longer back then. With today's ovens, five hours of cooking is enough.

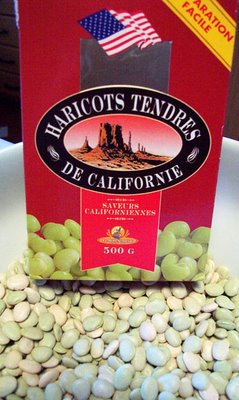

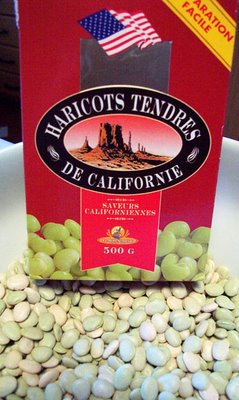

To serve with the lamb, which should be falling off the bone when it's done -- one chef says you could eat it with a spoon -- I'm going to cook some haricots tendres de Californie that I bought at the supermarket yesterday. Have you ever heard of "tender beans from California"? I never had. They are actually dried baby lima beans, I think.

I guess this is another example of fusion cooking -- French techniques with American ingredients.

I guess this is another example of fusion cooking -- French techniques with American ingredients.

I'm making it today. I had a gigot from one of our friend Gisèle's lambs in the freezer. No, this time I don't know what the lamb's name was. She usually does give us that piece of information, but neglected to this time. I didn't ask.

Here's how it's done. You brown the leg of lamb on all sides -- I browned it under the broiler. The recipe I have printed out calls for including a pied de veau, but I didn't find one of those yesterday at the Atac supermarket in Amboise, so I bought a pied de porc instead and am using that. I put it in the pan with the gigot to brown under the broiler. I hope the pig's foot produces a good amount of gelatin as it cooks, to enrich the sauce. I think it will.

Somebody asked me if I knew what the pig's name was. Ha ha ha.

While the meat is browning, you chop some carrots and celery and cook them in a wok or sauteuse with a couple of small onions, seven or eight shallots, and seven or eight garlic cloves, all peeled but left whole. Add a couple of tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped (or not seeded if you don't want to -- I didn't). When the vegetables are starting to brown, deglaze the pan with a quart of veal broth if you have it -- I used turkey broth because that's what I had in the freezer. Chicken or vegetable broth would be good too.

When the gigot was browned a little, I poured the vegetables and stock over it in the pan and added some thyme, peppercorns, allspice berries, and bay leaves. I added another quart of broth so that the leg of lamb is sitting in a couple of inches of liquid. Then I covered the pan and put it in the oven.

Jean-Pierre Coffe and my Cuisine TV recipe both call for cooking the lamb for four to five hours in a slow oven (110ºC / 225ºF). Why do you call it a gigot de sept heures if you only cook it for five hours? the radio interviewer asked Coffe. Well, in the olden days it cooked on the edge of the stove or fireplace, where the temperature couldn't be regulated very precisely, Coffe said. It took longer back then. With today's ovens, five hours of cooking is enough.

To serve with the lamb, which should be falling off the bone when it's done -- one chef says you could eat it with a spoon -- I'm going to cook some haricots tendres de Californie that I bought at the supermarket yesterday. Have you ever heard of "tender beans from California"? I never had. They are actually dried baby lima beans, I think.

I guess this is another example of fusion cooking -- French techniques with American ingredients.

I guess this is another example of fusion cooking -- French techniques with American ingredients.06 February 2006

The house at La Renaudière

If you want to read this series of postings in chronological order, start here: Quitting California. It's the story of leaving California and buying a house in France. Click Next at the bottom of each article to jump to the next one in the series.

Here we were looking at house after house, not really knowing whether we were likely to buy something. As I said earlier, even after arriving in France I was telling Walt I wouldn’t be surprised if we didn’t see any houses at all during this week. Now it was Tuesday afternoon, and we had already seen six places that were for sale at prices under the maximum we had told Bourdais we could spend. What had started as an exploratory trip was getting very real. Especially Tuesday afternoon when we came up to la Renaudière, the hamlet where, three years later, we now live.

The house at la Renaudière shouldn’t even have been on the tour. It didn’t have enough bedrooms — only two. All the other houses had at least three, as we had specified, and one had five. But Bourdais wanted to show to us this one anyway. He had a feeling we might like it, especially what they call here the environnement. That’s what they say about real estate, isn’t it? The three most important factors in buying a house are (1) environnement, (2) environnment, and (3) environnement.

Bourdais was right. The hamlet is nice and quiet but only 3 km (2 miles) from the center of Saint-Aignan. It is about half a mile, just less than a kilometer, off the main road (which I wouldn’t even call a highway — it’s a country road) up a lane that passes in front of some houses down below, climbs up a hill through a little wooded area, and then arrives at a settlement made up of eight houses.

The house has a name dating back to the time when there were no street numbers in the village. That wasn’t very long ago because the house was built in the late 1960s. It’s called Les Bouleaux, The Birches, because there are birch trees all around. It’s the last house on the right on the paved road, which becomes a gravel road running out into the vineyards right at the back of the property. In other words, there’s no car or truck traffic except for the few vehicles going to our neighbors’ houses and the tractors used for working the vines at harvest time.

The property itself is just over half an acre — 2300 square meters — and is bordered by a nice hedge on three sides, making the yard almost completely private. On two sides, it is surrounded by vineyards. Another side is the little country lane that is called the rue de la Renaudière, and on the east side a hedge and a fence separate our yard from the neighbor’s.

Most importantly, the yard is basically flat. And it was already nicely landscaped when we saw it, with gravel paths and fruit trees and even a dozen or so grape vines planted in nice rows. It was all green, even in December.There’s a solidly built, concrete garden shed on a little concrete slab. There’s a garage that could hold two cars (and now holds a lot of boxes and other junk) and there’s a carport that we now use as a shed to store firewood.

So the setting or environnement is just what we were looking for. The house, too, has many strong points. First of all, it’s old enough to have a little bit of character, but not so old that it needs major upgrades. It’s not a cookie-cutter model, as several others we saw were, with the same basic layout — a living room and then a long narrow hallway off which there are three or more bedrooms and a bathroom.

The house has a downstairs entryway and then a handsome travertine staircase leading up to the main living area. Upstairs there’s a big landing with French doors leading into a large living/dining room, which measures about 425 sq. ft. There’s a big fireplace. The kitchen is not tiny but certainly not huge, and it came with cabinets and a sink already installed. There’s a huge bathroom with a big tub and there’s a separate half-bath or WC room.

The only shower stall was the one in the big utility room downstairs, where the water heater and boiler for central heating are located — but at least there was a shower. The water heater and boiler looked fairly new. There’s good-sized pantry for storing wine and grocery items, and there’s a big garage as I said.

The bedrooms are small, but big enough. One has handy built-in cabinets on two walls, which we kept. Throughout, with the exception of one bedroom, the floors are ceramic tile that is not particularly attractive overall — there are too many patterns in it in different areas — but that is in very good shape. The one bedroom had vinyl or asphalt tile on the floor; we figured we could have that one carpeted. There was also plenty of ugly old wallpaper that needed to be removed.

The other nice feature of the house is a big deck or terrasse on the front off the living room, which in summer greatly increases the living space. The terrasse was in bad shape when we first saw the house, however. The previous owners had put down green outdoor carpeting on it, and it had absorbed a lot of moisture and started to mildew. That was covered with tarps held down by heavy boards and concrete blocks. It was awful, but had great potential. One of the first improvements we made when we took possession of the place was to have ceramic tile put down out there.

The other really nice feature of the house is its big windows all around. In fact, Josette, the woman who owned it before us, told us she always thought the windows were too big for the rooms. What she meant, I think, is that French windows are hinged on the side and open into the room. In the two bedrooms, the windows are so big that when you opened them they swept over most of the room. That made it difficult to put furniture near them, and made it impossible to sleep with the windows open on hot summer nights. If you tried it and got up in the dark during the night, you were risking a serious accient. We solved that problem later by having double-glazed sliding windows put in to replace the old French ones.

The living room has a very large three-panel French window on the north side, and a huge four-panel French door across the east wall leading out onto the deck.

Anyway, this place wasn’t like any of the other houses we had seen. It was more open, with a big salle de séjour (living/dining room), a big deck, and a lot of light from all the big windows. The bathroom was huge, and that’s a luxury here, where all the bathrooms I have ever seen have been little closets, especially in Paris apartments. This bathroom was much bigger that the ones in our San Francisco house.

Walt and I exchanged a glance as soon as we started looking around the house. “This is the one,” it meant. The same thing had happened in San Francisco in 1995 when, after spending a couple of months going to open houses around the city when we were looking for a place to buy, we first saw the house we ended up buying and living in for the last eight years we were in California. We looked at each other and knew immediately we had found the place we were looking for. It was a good feeling, but we hadn’t expected it to happen so fast on this trip.

This house at la Renaudière also had a huge attic and room for a staircase to be put in for access. Bourdais said we could buy the house, have the attic space finished off and the staircase put in, and still not go over our budget.

That was because this house was listed at 33% less than we had said our top offer would be, and a good 20% less than any of the other five houses we had already seen. I asked Bourdais why the owner was asking so little for it. “She just wants to sell it now,” he said. Her husband had died a couple of years before, and she lived in an apartment in Saint-Aignan. She and her husband had used the house as a summer place. They were both on their second marriages, and the husband and his first wife had had the house built as a place for their retirement before she was killed in an automobile accident in Morroco in the late 1970s.

I don’t think the second wife felt any particular attachment to the place. We have become friends with her, and since we bought the house she has sold her apartment in Saint-Aignan, where she was bored and lonely, and bought an apartment in Tours in the same neighborhood where her daughter, son-in-law, and grand-daughter live. She was trying to liquidate her holdings in Saint-Aignan quickly, as it turned out, and we were the beneficiaries.

We didn’t spend a lot of time in the house and yard that Tuesday afternoon. I did take pictures, however, and all this ones in this blog entry are ones I took that first afternoon and two days later. The house had been closed up and unoccupied for at least two years at that point, and probably longer, so it was musty-smelling and kind of a mess. But it was pretty much empty, and you could see how much space there was.

This was not really a dream house for us. We were looking for an affordable, pleasant place to live, in a nice location in France. We figured we could do painting and clean-up work to make the place our own. However, we didn’t really want to undertake major renovations.

We were thinking in terms of escaping from the rat race and from the high cost of living in the San Francisco area. We liked living there, but I didn’t know if I could face the prospect of commuting again. We loved our San Francisco house. We didn’t know when we would actually move — our plan still was to see if we could afford to buy a place for our retirement, whenever that day might come. Meanwhile, we would use it as a vacation place, or I would move here and Walt would stay and work, or ... well, there were a thousand possibilities, we thought. Or I thought. You’d have to ask Walt what he thought.

Besides, it had not really dawned on us yet that we might actually buy a house on this short exploratory trip. We still had a day or two of house tours ahead of us.

Next: It all starts to blur

05 February 2006

Seeing Saint-Aignan for the first time

The nature of blogs is that you read forward, not backward. The problem is that this is the fourth in a series of articles. If you want to read them in order, use these links. Then click Next at the bottom of each article to jump to the next one in the series.

We drove back to the gîte after our first day of house-hunting wondering what Saint-Aignan would be like. If houses were less expensive there, as Bourdais seemed to me to be implying, maybe it wasn’t a desirable location. “Maybe it’s some kind of ville nouvelle, all Soviet-style 1960s architecture, big apartment blocks. Maybe it’s an industrial center. Maybe it’s a ghost town,” I told Walt. Always the optimist, I am. My vision of France was skewed by my familiarity with Paris and its banlieues.

Back at the gîte we got out the map and studied it. It was true that Saint-Aignan-sur-Cher was just ten miles upriver from Montrichard, on the opposite bank. There was nothing near it that we were familiar with, except Valençay, where there is a famous château.

We had lunch in Valençay in October 2000 and enjoyed it. The restaurant was very old-fashioned and the other customers, especially one very bourgeois-looking French woman who was seated facing us, stared at us with cold eyes as we sat waiting to be brought menus. We felt like aliens and wondered what she was looking at. We don’t know if it was because we were two men, because we looked American, or because we weren’t dressed properly. Or maybe she wasn’t looking at us at all. We had a good lunch anyway, with a bottle of the local Valençay VDQS red wine.

Would Saint-Aignan be as old-fashioned as Valençay had seemed? That would be fine with me. I can stare at foreigners with the best of them -- or even at French people all dressed up in their Sunday best. I kind of liked the idea. We decided that since we had Tuesday morning free, the smart thing to do would be to drive over to Saint-Aignan and have a look around. If we hated it, we could tell Bourdais at our 2:30 meeting that we’d rather see houses closer to Montrichard — which didn’t seem old-fashioned and formal but bustling and friendly — or closer to Amboise, which is where we had wanted to start anyway.

I don’t remember by what route we drove to Saint-Aignan the next morning. Now I know that there are several ways to get here from Amboise or even from Montrichard. I suppose we took the main road, which is the route nationale 76 that runs along the Cher river south of Montrichard, crosses the Cher near the village called Thésée, and then runs along the river north of Saint-Aignan through the town called Noyers-sur-Cher. The stretch from Montrichard to Thésée is especially nice, and is marked as scenic on Michelin maps.

The river valley is wide and open. The banks of the river are wooded, so you don’t actually see the water. On the left are wide fields where sometimes you see the local roe deer grazing. On the right side there are picturesque houses and at least a couple of churches (in the wine villages of Angé and Pouillé) along a secondary road that parallels the route nationale. The houses are built up on wooded bluffs that mark the southern limit of the river valley. To the north, you see the hills on the other edge of the river valley, some of them planted in vines. When you get to Thésée (another wine village) you can see the village church steeple off in the distance, just before you cross the highway bridge over the Cher, where you have a nice view of the river itself.

When you cross over to the north bank of the river, you come fairly soon to a less attractive area. There is a big grain elevator off to the left. Up close, it looks like ... well, a grain elevator. You could be in the American Midwest, or the Central Valley of California. But I maintain now that, from a distance, that elevator looks almost like a big cathedral church. The local people have been known to laugh when I say that. Anyway, the next thing you see is a fairly ordinary looking shopping center on the left hand side of the road -- Intermarché, Bricomarché, L’Univers des Affaires, Sésame, a couple of furniture stores and other businesses, all in corrugated steel buildings that are basically warehouses. There’s also a plant where nut oils are pressed and bottled.

But it you look off to the right as you are driving past the grain elevator and the centre commercial, you can see the massive château de Saint-Aignan sitting up on a high bluff above the river and the town.

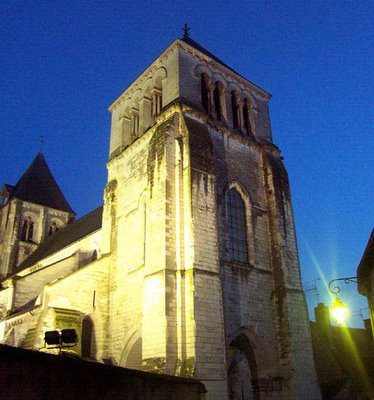

You come to a carrefour giratoire — a traffic circle or roundabout or rotary or whatever you call it — and you take the first road to the right into Saint-Aignan. As you drive in, you are faced with the château high above the bridge and river, and as you come to the old bridge across the Cher there is the big old church off to the left. Saint-Aignan is definitely not about 1960s-style Soviet apartment blocks, and it is not an industrial town. It couldn’t be more typical, ancient French. Cobblestone streets. Houses from the 15th century. A church from the 11th century, and the ruins of a château dating back even further, along with the 16th century Renaissance château.

We drove around the town — very small, with a population of 3500 — and knew right off that it was fine. We were not disappointed. It didn’t seem quite as animated as Montrichard, but that was okay. It obviously had all the standard shops — pharmacies, banks, butcher shops, charcuteries, bakeries, a bookstore, a newspaper and magazine shop, restaurants, cafés, hotels, and so on. I don’t know if we took or had the time to walk around — maybe it was too cold and we just stayed in the car. We were still a little dazed and confused.

You can see some pictures of Saint-Aignan here, along with many others scattered through my old photo site and this blog. You can read about the practical side of living in Saint-Aignan here.

There was a hotel/restaurant on the banks of the river near the bridge called the Hôtel du Moulin. The sign out front said lunch was 10 euros per person -- that was $10.00 back then. We decided to try it. We entered by the front door, and there was a bar at a diagonal across the room, with a few café tables. We were directed into a dining room off to the left. There must have been 15 or 20 tables in the dining room. We sat at one. Most but not all the others were already taken. The meal was a set menu with no choices. I remember that there was a pasta salad, with grated carrots in it. It was fine. I think we had chicken in a sauce as the main course, with green beans. There was salad and cheese afterwards, and a dessert. Wine — un quart de litre par personne — was included in the price. Coffee was extra. All in all, it was a satisfactory experience. I kept thinking that, if we lived here, I could come here for lunch every day without breaking the bank and be perfectly happy with the food.

The fact is that I’ve never returned to the restaurant at the Hôtel du Moulin. I’m not sure why, except for the fact that we don’t go out to eat much. The price of the lunch has gone up to €11.00 since then. There is another restaurant in Saint-Aignan that offers in a similar deal, and there’s one across the river in Noyers-sur-Cher that does the same. The menu at the restaurant in Noyers has an hors-d’œuvre buffet -- a salad bar -- where you can eat as much as you want before your main course comes, or which you can have as your whole meal for just eight euros. It has two choices for the main course, and the lunch costs fifty eurocents less than the lunch at the Hôtel du Moulin. It too includes wine. The food is good. We drove back to Montrichard after lunch and arrived at Bourdais’ office for our 2:30 appointment. We were ready to see houses near Saint-Aignan.

The first place he showed us was actually in Thésée, across the river and just a little west of Saint-Aignan. It was the first house where I thought we might be on the right track. It was fairly new, with a modern kitchen that showed some signs of wear and tear but was fundamentally nice. It had three bedrooms upstairs, but you had to walk through one of them to get to another one -- the people living there had children and they used those two bedrooms. The master bedroom was independent and private. I don’t remember if there was a bathroom upstairs -- there must have been.

This house sat on 2 or 3 acres of land, if I remember correctly. The people had horses and there were several outbuildings. Most of the land was used as pasture. On the down side, the house was completely exposed to the road, with no privacy fences or hedges. There was a concrete patio on the back of the house that had a lot of green mold or algae growing on it — that was probably something we could deal with. And the train tracks were very close, so if you lived there you would definitely hear the trains go by. Both passenger and freight trains run on that line.

Across the street, there was a warehouse-type building, which Bourdais told us was a bakery where breads and croissants and other pastries were baked for sale in local farmers markets. He said it would smell really good in the morning. We left thinking that that house was a good possibility for us, though not ideal. It was too much land, really, with nothing on it but horses, which we didn’t plan to keep.

Then we drove over to see houses in a couple of villages closer to Saint-Aignan. First we inspected a house on the side of a hill that had something like five small bedrooms, a small living room, a small dining room, and a kitchen that was just an empty room. It was carpeted throughout with gold-colored shag carpet, very 1970s, and the wallpaper all needed to be redone. There were neighboring houses close by. There was a big garage underneath.

The biggest negative of this house was that the back yard went straight up a hill. It had been nicely landscaped at some point, with little paths and hedges and birdbaths. It had probably been very beautiful, but it was completely overgrown when we saw it. Living on the side of a hill like that is a problem for two reasons. Water runoff is a danger. The other problem is that the yard is basically useless for gardening. We're talking about a very steep hill.

Our house in San Francisco was on a hill like that. Once, when we had very heavy rain for a couple of days, we had water flowing from the back yard, up above the house on the hillside, down under the house and pouring like a fast-flowing stream into our garage and under our electric washer and dryer. We wondered whether the foundations were going to be undermined. We had to scramble to move a lot of things we had stored in the garage to prevent them from being ruined by the water. Luckily there were drains in the garage floor to take the water out of the building. Our next-door neighbor told us she had water flowing under her house and into her garage every time it rained. At least ours was just a one-time occurrence in the eight years we lived there.

Another house we saw here in the Saint-Aignan area confirmed the dangers of living on a hill. Its basement had an inch or two of water covering the floor. We ruled that one out immediately for that reason, but also because there were neighbors too close, and because the property, again, was on a fairly steep hill. It would have been a nice place otherwise — it was within easy walking distance of the village center, where there’s a bread bakery, a grocery store, a café, a post office, and a public library. And it was a fairly nice house, though in need of serious decorating upgrades.

The other house we saw that Tuesday afternoon is the one we decided to make an offer on.

02 February 2006

Monday in Montrichard

Monday, December 9, 2002. We woke up groggy in our gîte in Pocé-sur-Cisse, on the northern outskirts of Amboise. We had an 11:00 a.m. appointment with a realtor in Montrichard, 12 or 15 miles south.

Each time we saw Adrienne or Jean, the owners of our gîte, she or he would ask what we were planning to go see and whether we needed suggestions or driving directions. We were being very vague with them, because we didn't want to announce that we had come to buy a house for fear of jinxing the whole plan, or looking naive if we couldn't find anything. We were keeping the whole enterprise a secret for the time being. I think Adrienne and Jean thought we were dazed and confused, since we wouldn't really answer their questions or accept their help on our "tour" of the region.

And we were groggy from jet lag, that’s for sure. But Walt was in worse shape than that. He had some kind of sinus affliction that kept him from getting much sleep at all. Everytime he would lie down to sleep, his throat would get irritated and he would start coughing. He’d have to get back up, drink some water, walk around for a while. Once he could stop coughing, he’d try again. Same scenario. It was miserable. I was disoriented with jet lag and fatigue, but at least I wasn’t coughing.

We drove our Peugeot over to Montrichard on a nice road through the forêt d'Amboise and found a place to park on the main street, rue Nationale, where the Vallée du Cher realty office is located. I think we arrived right on time. I still half expected to be told there was a problem with the appointment and to be asked to come back later in the day or even later in the week. We had only five days for our house hunt, because we had to fly back to California the next weekend, so any delay would be serious. Walt had to get back to work.

At the realtor's, the young receptionist greeted us enthusiastically. She was expecting us, and Monsieur Bourdais would ‘receive’ us in just a few minutes. Could we wait? Well, of course. I was relieved to see that the atmosphere in the office was cheerful and informal rather than cold and stiff.

Monsieur Bourdais, an energetic, refined, and friendly 40-something man, was, it turned out, the owner of the Vallée du Cher agency. He had decided to deal with us personally, as we learned later, because he spoke English better than any of the agents in his employ. He didn’t know how much French we spoke, he said, even though our e-mail exchanges had taken place in French. We were lucky it turned out this way.

Come upstairs to my office, he said, so we can talk about what kind of property you are looking for. We followed him up a narrow staircase to the front office on the premier étage of the building. It was a decent-size room with a big desk and a couple of chairs for visitors. The window overlooked the rue Nationale.

Bourdais asked us to describe what we were looking for. We told him we wanted a house in the country, with good privacy, but not too far from a town with tous les commerces — all the customary shops, including grocery stores, bakeries, and so on. We wanted three bedrooms or more, and we wanted a yard where we could have a vegetable garden.

Did we plan to entertain a lot, he asked? If so, we would want a large living room. And how much are you thinking of spending? We told him, and I was almost embarrassed at how low the figure sounded. “Nous avons un budget que nous ne pouvons pas dépasser” — we have to stick to our budget, I told him. “Tout le monde a un budget, vous savez” — everybody has a budget, you know, is what he answered.

That made me feel better. I realized our budget was pretty low, but I didn’t want us to get in over our heads. We weren’t sure when or even if we might actually one day move to France, so there was no need to take on a huge mortgage. Remember, I was unemployed. Besides, I had seen a lot of houses for sale in our price range on the company’s web site.

Bourdais pulled out a big thick binder full of printouts of house descriptions and photos. His office staff obviously used a color inkjet printer. He said he had about 400 properties for sale in his portfolio within 25 km (15 miles) of Montrichard. While we sat and watched in silence from across the desk, he spent at least 15 or 20 minutes — it seemed longer — thumbing through the binder, reading descriptions, and putting post-it tabs on the properties he thought might be right for us.

When he had finished, he had indexed about twenty houses. He started showing us the pages and photos, and we narrowed it down to a dozen or so places that we thought looked promising. All were priced under our maximum, with maybe one exception. That one, he said, he thought we could at least make an offer on without going over budget. He said he would show us the 12 properties before the end of the week. Would we like to come back at 2:30 and start touring around?

It was 12:30 and we were ready for lunch. Just a couple of doors down from the real estate office was a pizzeria that looked promising. We went in and got a table and ordered. It was one of those typical French places, small and crowded and warm on a chilly winter day. Bustling. I don’t remember what we ate, but it was good. While we were eating, we looked up and saw Bourdais in the restaurant, and we nodded and smiled at each other. I can’t remember whether he had just finished his meal or whether he was picking up something to take back to his office.

At 2:30 we went back to the office. He said he’d like to show us two houses in Montrichard itself. The first was up on the road that goes to Amboise, just a few hundred yards after you cross the railroad tracks, up on the right. In Montrichard there is a huge retirement complex up on the hill overlooking the town and the Cher river valley. The place we were going to look at bordered on the retirement complex property, which Bourdais said was an advantage. That land was like parkland, and wasn’t likely to be developed in the foreseeable future.

We arrived at the house, just 100 meters off the Amboise road, in Bourdais' Audi. There was a gate across the driveway, and it was locked. Bourdais tried several keys but couldn’t get the gate open. He looked at us and said, well, are you willing to climb over the wall? It wasn’t very high, so we said why not? I hoped he hadn't taken us to the wrong house. What had we gotten ourselves into? Over we climbed.

The house itself was not what we were looking for. First of all, there were a lot of other houses really close by. The yard was big, but it was on a hillside and was divided up into several oddly shaped plots, one of which was a narrow strip that ran down the hill to to the Amboise road, where there was a gate. It was true, as Bourdais pointed out, that we could have a good garden there — it had a southern exposure. But it also was completely exposed to the neighboring houses.

The first house we saw was the plain-looking one in the middle of

The first house we saw was the plain-looking one in the middle of

this picture, with the retirement complex up above it

The house itself needed a lot of paint and polish. There was a central hallway, off of which we saw a small dining room, a small living room, and a couple of bedrooms. The kitchen was a medium-sized, totally empty room — no cabinets, no appliances, no sink. It needed a new floor, I think. All over the house there was ugly carpeting that needed to be removed. There was no telling what the floors under the carpeting looked like.

One of the worst things about the house was the view. It overlooked two modern apartment buildings down on the Amboise road. I think they are subsidized housing, but I'm not sure. There was a good view of the river valley beyond them, but the apartment buildings, blocky and tall, attracted your eye and blinded you to the rest. On the plus side, there was a SuperU supermarket not far away, and the house was within easy walking distance of the Montrichard train station.

But it was not an auspicious beginning. Okay, it was only the first house. At least Bourdais had been able to find the key that opened the front door, so that climbing over the wall didn't turn out to be a complete waste of time.

Next we drove down the hill back toward downtown Montrichard, but instead of turning left at the stop sign, just past the old church and cemetery, we turned right onto the road that goes to Chenonceaux (the château is only 6 or 7 miles to the west). Then almost immediately we turned left and drove down a long street lined with platanes, plane trees, all cropped in the French style. We came to the road that runs parallel to the river and turned right. It was a more or less suburban, residential neighborhood.

The house we were going to see was on the side of the road farthest from the banks of the river, across the street from a campground. The campground was of course empty on this December day, but we immediately imagined it crowded with noisy campers partying on summer evenings. The house itself was attractive enough from the outside — two stories, very French, a big yard. The main living area was on the second floor, as it is in the house ended up buying. The elderly woman who lived there was at home. That surprised us, because in San Francisco the people who are selling their house are always asked to leave when potential buyers are coming to see the place.

The woman’s husband had passed away recently, and she was going to move into a retirement home. The house was stuffed full of furniture and knicknacks. The rooms were small. It was all dark and kind of gray. No lights were on, and some of the windows were shuttered (that’s typical here). The kitchen needed work, but at least it had cabinets and a sink. It seemed small and crowded. There was a fireplace in the main room, but it was strangely placed so that you couldn’t really enjoy it from the sitting area. It was only visible from the dining area, which was closest to the hallway and kitchen. It wasn’t a very spacious room. I think there were two bedrooms — it’s hard to remember.

On the ground floor, there was also some improvised living space, including a little sitting area, what is called a cuisine d’été (a summer kitchen), and a bedroom for guests. But none of it was really completely finished off. Concrete block walls and rugs on poured concrete floors were the style of the downstairs — it was a basement. There were areas where a lot of boxes full of who-knows-what were piled in corners.

We also went up into the attic, which was unfinished space. It was spacious and could be turned into more living space, Bourdais said. There was fiberglass insulation just laid on the attic floor, in with its paper backing turned up.

House number two was across from a campground and down the road from

House number two was across from a campground and down the road from

an encampment where a group of gens du voyage were living in their caravans

Somehow, the river and flooding came into the conversation. The woman told us that in the last flood, two years earlier, the water had only come up to the front door but hadn’t actually come into the house. She showed us how far up it had come. It didn't inspire confidence.

Next door, there was a long, narrow strip of land that was partly planted as a vegetable garden and partly covered in what you could only call junk — an old car, I think, piles of rocks or paving stones, firewood, and farm equipment. It wasn't a junk yard but it was definitely had a rural appearance. The neighbor's house was on the back end of the lot, a couple of hundred meters from the road. I guess it was far enough from the river to avoid having water come up to its front door during floods.

Oh, the house we were looking at had an enormous back yard. It was nicely planted with fruit trees. It was flat ground (if a little soggy). That was a plus. But it wasn't at all private.

As we said au revoir to the owner and got into the car, Bourdais said he needed to point out to us that there was a gypsy camp just up the road about a kilometer. He took us to see it and explained that one of the gypsy elders had died on that spot a few years before, so it was considered sacred ground by his descendants. They would always return to that location every year and stay a while. Since the road we were on dead-ended at the encampment, the only way in was the road that passed by the house we had just looked at. Disclosing all that was a legal obligation, I think.

We drove back to the realty office. I was feeling a little discouraged. When we got there, Bourdais asked us what we thought. We said we wanted to continue looking.

Good, he said. I’d like to show you some houses over near Saint-Aignan, which is only 10 miles up the river. There are some good prospects over there.

Fine, we said. We had never heard of Saint-Aignan. Or if we had we didn't remember it. I needed to look at a map. Bourdais asked us to come back at 2:30 the next day.

Each time we saw Adrienne or Jean, the owners of our gîte, she or he would ask what we were planning to go see and whether we needed suggestions or driving directions. We were being very vague with them, because we didn't want to announce that we had come to buy a house for fear of jinxing the whole plan, or looking naive if we couldn't find anything. We were keeping the whole enterprise a secret for the time being. I think Adrienne and Jean thought we were dazed and confused, since we wouldn't really answer their questions or accept their help on our "tour" of the region.

And we were groggy from jet lag, that’s for sure. But Walt was in worse shape than that. He had some kind of sinus affliction that kept him from getting much sleep at all. Everytime he would lie down to sleep, his throat would get irritated and he would start coughing. He’d have to get back up, drink some water, walk around for a while. Once he could stop coughing, he’d try again. Same scenario. It was miserable. I was disoriented with jet lag and fatigue, but at least I wasn’t coughing.

We drove our Peugeot over to Montrichard on a nice road through the forêt d'Amboise and found a place to park on the main street, rue Nationale, where the Vallée du Cher realty office is located. I think we arrived right on time. I still half expected to be told there was a problem with the appointment and to be asked to come back later in the day or even later in the week. We had only five days for our house hunt, because we had to fly back to California the next weekend, so any delay would be serious. Walt had to get back to work.

At the realtor's, the young receptionist greeted us enthusiastically. She was expecting us, and Monsieur Bourdais would ‘receive’ us in just a few minutes. Could we wait? Well, of course. I was relieved to see that the atmosphere in the office was cheerful and informal rather than cold and stiff.

Monsieur Bourdais, an energetic, refined, and friendly 40-something man, was, it turned out, the owner of the Vallée du Cher agency. He had decided to deal with us personally, as we learned later, because he spoke English better than any of the agents in his employ. He didn’t know how much French we spoke, he said, even though our e-mail exchanges had taken place in French. We were lucky it turned out this way.

Come upstairs to my office, he said, so we can talk about what kind of property you are looking for. We followed him up a narrow staircase to the front office on the premier étage of the building. It was a decent-size room with a big desk and a couple of chairs for visitors. The window overlooked the rue Nationale.

Bourdais asked us to describe what we were looking for. We told him we wanted a house in the country, with good privacy, but not too far from a town with tous les commerces — all the customary shops, including grocery stores, bakeries, and so on. We wanted three bedrooms or more, and we wanted a yard where we could have a vegetable garden.

Did we plan to entertain a lot, he asked? If so, we would want a large living room. And how much are you thinking of spending? We told him, and I was almost embarrassed at how low the figure sounded. “Nous avons un budget que nous ne pouvons pas dépasser” — we have to stick to our budget, I told him. “Tout le monde a un budget, vous savez” — everybody has a budget, you know, is what he answered.

That made me feel better. I realized our budget was pretty low, but I didn’t want us to get in over our heads. We weren’t sure when or even if we might actually one day move to France, so there was no need to take on a huge mortgage. Remember, I was unemployed. Besides, I had seen a lot of houses for sale in our price range on the company’s web site.

Bourdais pulled out a big thick binder full of printouts of house descriptions and photos. His office staff obviously used a color inkjet printer. He said he had about 400 properties for sale in his portfolio within 25 km (15 miles) of Montrichard. While we sat and watched in silence from across the desk, he spent at least 15 or 20 minutes — it seemed longer — thumbing through the binder, reading descriptions, and putting post-it tabs on the properties he thought might be right for us.

When he had finished, he had indexed about twenty houses. He started showing us the pages and photos, and we narrowed it down to a dozen or so places that we thought looked promising. All were priced under our maximum, with maybe one exception. That one, he said, he thought we could at least make an offer on without going over budget. He said he would show us the 12 properties before the end of the week. Would we like to come back at 2:30 and start touring around?

It was 12:30 and we were ready for lunch. Just a couple of doors down from the real estate office was a pizzeria that looked promising. We went in and got a table and ordered. It was one of those typical French places, small and crowded and warm on a chilly winter day. Bustling. I don’t remember what we ate, but it was good. While we were eating, we looked up and saw Bourdais in the restaurant, and we nodded and smiled at each other. I can’t remember whether he had just finished his meal or whether he was picking up something to take back to his office.

At 2:30 we went back to the office. He said he’d like to show us two houses in Montrichard itself. The first was up on the road that goes to Amboise, just a few hundred yards after you cross the railroad tracks, up on the right. In Montrichard there is a huge retirement complex up on the hill overlooking the town and the Cher river valley. The place we were going to look at bordered on the retirement complex property, which Bourdais said was an advantage. That land was like parkland, and wasn’t likely to be developed in the foreseeable future.

We arrived at the house, just 100 meters off the Amboise road, in Bourdais' Audi. There was a gate across the driveway, and it was locked. Bourdais tried several keys but couldn’t get the gate open. He looked at us and said, well, are you willing to climb over the wall? It wasn’t very high, so we said why not? I hoped he hadn't taken us to the wrong house. What had we gotten ourselves into? Over we climbed.

The house itself was not what we were looking for. First of all, there were a lot of other houses really close by. The yard was big, but it was on a hillside and was divided up into several oddly shaped plots, one of which was a narrow strip that ran down the hill to to the Amboise road, where there was a gate. It was true, as Bourdais pointed out, that we could have a good garden there — it had a southern exposure. But it also was completely exposed to the neighboring houses.

The first house we saw was the plain-looking one in the middle of

The first house we saw was the plain-looking one in the middle ofthis picture, with the retirement complex up above it

The house itself needed a lot of paint and polish. There was a central hallway, off of which we saw a small dining room, a small living room, and a couple of bedrooms. The kitchen was a medium-sized, totally empty room — no cabinets, no appliances, no sink. It needed a new floor, I think. All over the house there was ugly carpeting that needed to be removed. There was no telling what the floors under the carpeting looked like.

One of the worst things about the house was the view. It overlooked two modern apartment buildings down on the Amboise road. I think they are subsidized housing, but I'm not sure. There was a good view of the river valley beyond them, but the apartment buildings, blocky and tall, attracted your eye and blinded you to the rest. On the plus side, there was a SuperU supermarket not far away, and the house was within easy walking distance of the Montrichard train station.

But it was not an auspicious beginning. Okay, it was only the first house. At least Bourdais had been able to find the key that opened the front door, so that climbing over the wall didn't turn out to be a complete waste of time.

Next we drove down the hill back toward downtown Montrichard, but instead of turning left at the stop sign, just past the old church and cemetery, we turned right onto the road that goes to Chenonceaux (the château is only 6 or 7 miles to the west). Then almost immediately we turned left and drove down a long street lined with platanes, plane trees, all cropped in the French style. We came to the road that runs parallel to the river and turned right. It was a more or less suburban, residential neighborhood.

The house we were going to see was on the side of the road farthest from the banks of the river, across the street from a campground. The campground was of course empty on this December day, but we immediately imagined it crowded with noisy campers partying on summer evenings. The house itself was attractive enough from the outside — two stories, very French, a big yard. The main living area was on the second floor, as it is in the house ended up buying. The elderly woman who lived there was at home. That surprised us, because in San Francisco the people who are selling their house are always asked to leave when potential buyers are coming to see the place.

The woman’s husband had passed away recently, and she was going to move into a retirement home. The house was stuffed full of furniture and knicknacks. The rooms were small. It was all dark and kind of gray. No lights were on, and some of the windows were shuttered (that’s typical here). The kitchen needed work, but at least it had cabinets and a sink. It seemed small and crowded. There was a fireplace in the main room, but it was strangely placed so that you couldn’t really enjoy it from the sitting area. It was only visible from the dining area, which was closest to the hallway and kitchen. It wasn’t a very spacious room. I think there were two bedrooms — it’s hard to remember.

On the ground floor, there was also some improvised living space, including a little sitting area, what is called a cuisine d’été (a summer kitchen), and a bedroom for guests. But none of it was really completely finished off. Concrete block walls and rugs on poured concrete floors were the style of the downstairs — it was a basement. There were areas where a lot of boxes full of who-knows-what were piled in corners.

We also went up into the attic, which was unfinished space. It was spacious and could be turned into more living space, Bourdais said. There was fiberglass insulation just laid on the attic floor, in with its paper backing turned up.

House number two was across from a campground and down the road from

House number two was across from a campground and down the road froman encampment where a group of gens du voyage were living in their caravans

Somehow, the river and flooding came into the conversation. The woman told us that in the last flood, two years earlier, the water had only come up to the front door but hadn’t actually come into the house. She showed us how far up it had come. It didn't inspire confidence.

Next door, there was a long, narrow strip of land that was partly planted as a vegetable garden and partly covered in what you could only call junk — an old car, I think, piles of rocks or paving stones, firewood, and farm equipment. It wasn't a junk yard but it was definitely had a rural appearance. The neighbor's house was on the back end of the lot, a couple of hundred meters from the road. I guess it was far enough from the river to avoid having water come up to its front door during floods.

Oh, the house we were looking at had an enormous back yard. It was nicely planted with fruit trees. It was flat ground (if a little soggy). That was a plus. But it wasn't at all private.

As we said au revoir to the owner and got into the car, Bourdais said he needed to point out to us that there was a gypsy camp just up the road about a kilometer. He took us to see it and explained that one of the gypsy elders had died on that spot a few years before, so it was considered sacred ground by his descendants. They would always return to that location every year and stay a while. Since the road we were on dead-ended at the encampment, the only way in was the road that passed by the house we had just looked at. Disclosing all that was a legal obligation, I think.

We drove back to the realty office. I was feeling a little discouraged. When we got there, Bourdais asked us what we thought. We said we wanted to continue looking.

Good, he said. I’d like to show you some houses over near Saint-Aignan, which is only 10 miles up the river. There are some good prospects over there.

Fine, we said. We had never heard of Saint-Aignan. Or if we had we didn't remember it. I needed to look at a map. Bourdais asked us to come back at 2:30 the next day.

La Chandeleur

Today, February 2, is called la fête de la Chandeleur in France. It's the 40th day after Christmas, when according to Jewish tradition Mary took Jesus to the temple to be presented to the rabbis. Chandeleur comes from the term that gave us candle in English — candles were lit during the service in the temple.

In France, today is a day when everyone makes and eat crêpes among friends and family. Tradition has it that you are supposed to hold a coin in one hand and flip a crêpe in the pan with the other. That brings good luck and prosperity for the year. If the crêpe flips out of the pan, you are supposed to leave in when it falls for a year, until next February 2. Otherwise you'll have bad luck. I've never known anybody who left a crêpe lying on the floor or the stove for a year, but everybody I know does make crêpes on February 2. I'm going to do the same today.

Chandeleur is somehow related to the American groundhog day, because there is this proverb:

In France, today is a day when everyone makes and eat crêpes among friends and family. Tradition has it that you are supposed to hold a coin in one hand and flip a crêpe in the pan with the other. That brings good luck and prosperity for the year. If the crêpe flips out of the pan, you are supposed to leave in when it falls for a year, until next February 2. Otherwise you'll have bad luck. I've never known anybody who left a crêpe lying on the floor or the stove for a year, but everybody I know does make crêpes on February 2. I'm going to do the same today.

Chandeleur is somehow related to the American groundhog day, because there is this proverb:

A la Chandeleur, L'hiver s'apaise ou reprend vigueur.

On the Chandeleur, winter turns mild, or regains vigor.

On the Chandeleur, winter turns mild, or regains vigor.

31 January 2006

Mourning Coretta King

I am sad to learn that Coretta Scott King passed away yesterday. She was an inspirational figure. She did much to preserve her assassinated husband's legacy and continue his work.

In the early and mid-1980s, I worked as a writer and editor for the Africa press service of the U.S. Information Agency in Washington. I traveled several times to Atlanta to do reporting at the King Center for Non-Violent Social Change. Mrs. King and Martin Luther King's sister Christine Farris were both unfailingly welcoming and forthcoming with information about the center's activities and goals.

Given the Reagan administration's suspicious and negative attitudes towards King and the U.S. civil rights movement, it was surprising to me that I would be received so kindly and openly at the King Center. I worked for Reagan, after all (that's a pretty embarrassing admission on my part). If you remember, when asked in 1983, during a press conference at the time that the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday was being instituted by an act of Congress, whether he agreed with Senator Jesse Helms' charge that King was a communist, Reagan replied: "We'll know in about thirty-five years." He was referring to FBI surveillance tapes on King that a court had ordered sealed until 2027. There he went again! Reagan missed a great opportunity to just say no, I don't think King was a communist. It was a pointless and insulting comment by the U.S. President.

I spent a week at the King Center in 1984 or '85 and wrote an article about the center, which had only recently opened, for a U.S. government publication. The slanted editing that my USIA editors did on that text was a big factor in my decision to leave the USIA a year or so later. But the article, my original version, was eventually reprinted in a magazine published by the Smithsonian Institution, and Coretta King was asked to review it.

Around that time, I was assigned by USIA to cover a press conference Mrs. King was holding in Washington DC at the Department of Education. At the conclusion of the press event, Mrs. King stayed to answer questions informally. I went and spoke to her privately. She remembered me, at least vaguely, and she complimented me on the article, which she had just finished reading. She said she was surprised that I had been able to learn so much about the King Center in just one week. In reality, she and her sister-in-law deserved much of the credit for that, because they were so willing to spend time talking with me. Mrs. King's praise was one of the hightlights of my career as a political writer/propagandist for the U.S. government.

I read in the paper a few weeks ago that the King Center has fallen on hard times. That is also a sad development. I'm sure Mrs. King's declining health has been one of the reasons for the turmoil there.

In the early and mid-1980s, I worked as a writer and editor for the Africa press service of the U.S. Information Agency in Washington. I traveled several times to Atlanta to do reporting at the King Center for Non-Violent Social Change. Mrs. King and Martin Luther King's sister Christine Farris were both unfailingly welcoming and forthcoming with information about the center's activities and goals.

Given the Reagan administration's suspicious and negative attitudes towards King and the U.S. civil rights movement, it was surprising to me that I would be received so kindly and openly at the King Center. I worked for Reagan, after all (that's a pretty embarrassing admission on my part). If you remember, when asked in 1983, during a press conference at the time that the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday was being instituted by an act of Congress, whether he agreed with Senator Jesse Helms' charge that King was a communist, Reagan replied: "We'll know in about thirty-five years." He was referring to FBI surveillance tapes on King that a court had ordered sealed until 2027. There he went again! Reagan missed a great opportunity to just say no, I don't think King was a communist. It was a pointless and insulting comment by the U.S. President.

I spent a week at the King Center in 1984 or '85 and wrote an article about the center, which had only recently opened, for a U.S. government publication. The slanted editing that my USIA editors did on that text was a big factor in my decision to leave the USIA a year or so later. But the article, my original version, was eventually reprinted in a magazine published by the Smithsonian Institution, and Coretta King was asked to review it.

Around that time, I was assigned by USIA to cover a press conference Mrs. King was holding in Washington DC at the Department of Education. At the conclusion of the press event, Mrs. King stayed to answer questions informally. I went and spoke to her privately. She remembered me, at least vaguely, and she complimented me on the article, which she had just finished reading. She said she was surprised that I had been able to learn so much about the King Center in just one week. In reality, she and her sister-in-law deserved much of the credit for that, because they were so willing to spend time talking with me. Mrs. King's praise was one of the hightlights of my career as a political writer/propagandist for the U.S. government.

I read in the paper a few weeks ago that the King Center has fallen on hard times. That is also a sad development. I'm sure Mrs. King's declining health has been one of the reasons for the turmoil there.

Hooked on onions

We finished that 5 kg/12 lb. bag of onions we were working on. Today we went grocery shopping at Intermarché. I had onions on the shopping list. When I saw the price per kilo, I was shocked. 90 euro cents a kilo! Last time, chez Ed, I paid 85 euro cents for FIVE kilos.

Then I noticed that Intermarché had a 5 kg bag of onions for 1.95 euros. That's a lot more than the last 5 kg bag I bought, but a lot better than 90 cents a kilo.

So I'm working on using up (and enjoying) onions again. Some things never change.

And here, by the way, was this morning's sunrise.

Then I noticed that Intermarché had a 5 kg bag of onions for 1.95 euros. That's a lot more than the last 5 kg bag I bought, but a lot better than 90 cents a kilo.

So I'm working on using up (and enjoying) onions again. Some things never change.

And here, by the way, was this morning's sunrise.

Going to Amboise

Where in France? That was the question.

Walt and I had been spending our vacations in France since 1988. We had spent more time in Paris than anywhere else. But in 1989 we had done a driving tour in the south and southwest, visiting Grenoble, Nîmes, Narbonne, Carcassonne, Bordeaux, Cognac, Poitiers, and Chartres. That covered a lot of territory. In 1992, we did a driving tour of Normandy and Brittany, returning to Paris on a route that took us through the Loire Valley. In 1993, we spent two weeks in Provence. On that trip, we drove through Burdundy on the way south and through the Massif Central on the way back to Paris.

In 1994, we went on a day trip to Champagne, and in 1995 we spent 10 days near Cahors, with visits to Toulouse, Agen, Rocamadour, and Albi. We had friends in Normandy and on many trips we spent a few days with them while we were in France. In 1997, 1998, and 1999, we focused on Paris, renting apartments in the city for a couple of weeks at a time.

In October 2000, after deciding to abandon a plan to go spend two weeks in Alsace, we ended up renting a gîte (a small house rented for short stays) in Vouvray, near Tours in the Loire Valley. We spent a week in Vouvray, and then a week in Champagne, and another week in Paris. We liked Vouvray and the house we rented there so much that we decided to rent it again in June 2001, for two weeks. We loved it the second time, and traveled by car all over the region.

In September 2001, we returned to Provence for a two-week stay in a gîte near Cavaillon. In April 2002, we spent two weeks in an apartment in Paris, near Montparnasse, with another side trip to Normandy. The euro was new then, and it was very low against the dollar. Everything in Paris seemed very inexpensive then, compared to San Francisco. In addition, I had very severe springtime pollen allergies in California, but when we arrived in Paris all the symptoms went away. That had happened once before, when I went to Seattle for a conference in March. What a pleasure it was to be in Paris in the springtime!

I say all that just to make it clear that we knew France well and knew what different regions were like. We both understand and speak French well. I lived and worked in France for about eight years in the 1970s and early 1980s. Walt spent a year in Paris as a student in the early 1980s. We love French popular music and have a good collection of CDs that we listened to a lot -- that's a great way to improve your French comprehension and pronunciation. We had a French-language television channel (TV5) in San Francisco via satellite.

In October 2002, then, the French-countryside experience that was freshest in my mind was the place in Vouvray, in the Loire Valley. I had several reasons for not wanting to relocate to Provence or the French Southwest, among them the distance from Paris and the possibility that my pollen allergies might to be aggravated by plants native to the south of France. After our April 2002 trip to Paris and Normandy, my allergist in San Francisco had recommended that I leave California and go live either in the Pacific Northwest or northern France. Doctor's orders...

I was going to start researching real estate possibilities in the northern French countryside, and what better place to start with than the Loire Valley, then? We had enjoyed our vacations in Vouvray, and had toured around quite a bit from Angers to Chinon and Bourgueil, from Amboise and Montrichard to Blois, Chambord, and Romorantin.

Finding French real estate agencies on the Internet was easy. We decided to start looking around Amboise. It’s a beautiful town of about 15,000 people, and it’s far enough from Tours to be outside the suburban ring. Vouvray was nice, but it really is the suburbs of Tours these days. I quickly found quite a few houses for sale within 25 miles or so of Amboise that looked attractive and affordable. I studied several real estate sites, including FNAIM and ORPI.

After a few days of searching, I sent a couple of e-mails to real estate agents in Amboise. One answered promptly and said he would be glad to help me find a place to buy. This whole endeavor was starting to get serious. I told Walt we needed to schedule a trip to the Loire Valley to see if the houses I was seeing on Internet sites were all located near garbage dumps or in the shadow of nuclear power plants. He examined his schedule and we decided to go spend a week in Amboise in early December.

Early December is a good time to travel. The airlines offer good fares. It’s easy to find places to rent — we found a gîte on the northern outskirts of Amboise with no trouble. We rented it for a week for about $350. I wrote back to the real estate agent in Amboise who had answered my initial e-mail and told him we would like to come see some houses that week.

The fact was, I thought it was unlikely that we would see very many houses in one week. I’ve spent enough years in Paris to develop a tough sense of realism about how long it can take to get anything done in France. Things move slowly. I told Walt that we might get to Amboise only to find out the real estate agent was too busy to help us right then. We might spend a week there without seeing a single house. But what the heck, it was a week in France, n’est-ce pas? It was a good Christmas present to ourselves, if nothing else. We could at least drive around and look for "for sale" signs.

I told the agent in Amboise that we would be there on a Monday morning in early December, raring to go. He answered immediately and said that sounded good, but his office in Amboise was closed on Mondays. Would we mind coming to his office in Montrichard? It would be open that morning. We had visited Montrichard two years earlier, so we knew it was only 10 miles south of Amboise. We remembered it as a nice little town on the banks of the Cher River. I sent back an e-mail saying that coming to the office in Montrichard on that Monday was not a problem. He answered and said we had an 11:00 appointment.

When December came, we flew to Paris and arrived on a Saturday morning. We picked up a rental car (a nice Peugeot 307) at the airport and drove the three hours down to Amboise. The owners of the gîte we had rented had given us directions to their house, and we found it without too much trouble. We checked in and then immediately drove over to Vouvray, familiar territory seve or eight miles west, to visit the Atac supermarket that we had liked there. We bought milk, butter, sugar, mustard, vinegar, oil, and other staples for the kitchen. It felt good to be back in Vouvray.

The next morning, Sunday, there was a big food market in Amboise, the gîte owners told us, and it turned out that jet lag had us up and going early that day. We were at the market by 8:30 a.m. We bought what we needed and wanted to make lunch at the gîte, and then went back to prepare a hot meal. That afternoon, rather than give in to jet lag, we took a long walk around the area, looking at houses (even though they were not for sale) and talking about how much we liked this one or that one and how great it would be to live in such a place.

The weather was cold, gray, and damp. We were of course exhausted after the overnight flight. The gîte owners, Adrienne and Jean, told us there was plenty of firewood in the shed next to our place and said we should take what we wanted. Walt built a fire and we watched French television that Sunday evening, wondering what Monday was going to be like.

Walt and I had been spending our vacations in France since 1988. We had spent more time in Paris than anywhere else. But in 1989 we had done a driving tour in the south and southwest, visiting Grenoble, Nîmes, Narbonne, Carcassonne, Bordeaux, Cognac, Poitiers, and Chartres. That covered a lot of territory. In 1992, we did a driving tour of Normandy and Brittany, returning to Paris on a route that took us through the Loire Valley. In 1993, we spent two weeks in Provence. On that trip, we drove through Burdundy on the way south and through the Massif Central on the way back to Paris.

In 1994, we went on a day trip to Champagne, and in 1995 we spent 10 days near Cahors, with visits to Toulouse, Agen, Rocamadour, and Albi. We had friends in Normandy and on many trips we spent a few days with them while we were in France. In 1997, 1998, and 1999, we focused on Paris, renting apartments in the city for a couple of weeks at a time.

In October 2000, after deciding to abandon a plan to go spend two weeks in Alsace, we ended up renting a gîte (a small house rented for short stays) in Vouvray, near Tours in the Loire Valley. We spent a week in Vouvray, and then a week in Champagne, and another week in Paris. We liked Vouvray and the house we rented there so much that we decided to rent it again in June 2001, for two weeks. We loved it the second time, and traveled by car all over the region.

In September 2001, we returned to Provence for a two-week stay in a gîte near Cavaillon. In April 2002, we spent two weeks in an apartment in Paris, near Montparnasse, with another side trip to Normandy. The euro was new then, and it was very low against the dollar. Everything in Paris seemed very inexpensive then, compared to San Francisco. In addition, I had very severe springtime pollen allergies in California, but when we arrived in Paris all the symptoms went away. That had happened once before, when I went to Seattle for a conference in March. What a pleasure it was to be in Paris in the springtime!

I say all that just to make it clear that we knew France well and knew what different regions were like. We both understand and speak French well. I lived and worked in France for about eight years in the 1970s and early 1980s. Walt spent a year in Paris as a student in the early 1980s. We love French popular music and have a good collection of CDs that we listened to a lot -- that's a great way to improve your French comprehension and pronunciation. We had a French-language television channel (TV5) in San Francisco via satellite.

In October 2002, then, the French-countryside experience that was freshest in my mind was the place in Vouvray, in the Loire Valley. I had several reasons for not wanting to relocate to Provence or the French Southwest, among them the distance from Paris and the possibility that my pollen allergies might to be aggravated by plants native to the south of France. After our April 2002 trip to Paris and Normandy, my allergist in San Francisco had recommended that I leave California and go live either in the Pacific Northwest or northern France. Doctor's orders...