Le roi Philippe remained on the throne of France until his death in 1108 — a 48-year reign. He was the great-grandson of Hugues Capet, who as king of France from 987 to 996 was the founder of the Capetian dynasty. The last direct descendant of Charlemagne had failed to produce a male heir. Hugues Capet was elected king by an assembly of French noblemen.

Philippe 1er spent most of his long reign trying to keep his unruly vassals — the dukes and other noblemen who controlled one piece or other of territory around Paris — in line. He succeeded at least to an extent, because his descendants continued to rule France until 1328.

One of Philippe's vassals, the Duke of Normandy that the world came to call William the Conqueror, won the battle of Hastings and became king of England when Philippe had been king of France for just six years (and was 14 years old). Philippe and William (Guillaume, in French) made peace ten years later, when William promised he would quit trying to extend his realm by conquering Brittany. Evidently, Philippe spent years trying to provoke unrest and dissension within the Anglo-Norman kingdom as a way to reduce its threat to his own power.

When he was 20, Philippe was married to Bertha of Holland, and they had five children. Then in 1092, at the age of 40, he fell in love with Bertrade de Montfort. He repudiated Bertha. He married Bertrade and was excommunicated by Pope Urban II.

When he was 20, Philippe was married to Bertha of Holland, and they had five children. Then in 1092, at the age of 40, he fell in love with Bertrade de Montfort. He repudiated Bertha. He married Bertrade and was excommunicated by Pope Urban II.His excommunication prevented Philip from taking part in the First Crusade, which was launched in 1095 and which he didn't personally support because of his conflict with the papacy.

When Philip died in 1108 at the château of Melun, near Paris, his body was carried in a great procession from there to the abbey church at St-Benoît-sur-Loire, some 70 miles distant, where he wished to be buried.

When Philip died in 1108 at the château of Melun, near Paris, his body was carried in a great procession from there to the abbey church at St-Benoît-sur-Loire, some 70 miles distant, where he wished to be buried. The monastery at what is now called St-Benoît-sur-Loire had been founded four or five hundred years earlier. It was called Fleury then. In the late 600s, a group of monks from Fleury made the long trek to southern Italy and brought back some of the remains of St. Benedict (Benoît is French for Benedict). The bones that they found and carried back were certified as authentic by the pope at the time.

The monastery at what is now called St-Benoît-sur-Loire had been founded four or five hundred years earlier. It was called Fleury then. In the late 600s, a group of monks from Fleury made the long trek to southern Italy and brought back some of the remains of St. Benedict (Benoît is French for Benedict). The bones that they found and carried back were certified as authentic by the pope at the time. St-Benoît-sur-Loire became a very holy place in Christendom, given Benedict's stature as the founder of the great religious order that carries his name, the Benedictines. The saint's remains, or relics, according to the Michelin guide, were a "source of miracles, of healing, and many wonders that couldn't but draw crowds and spread the fame of the place from then on known as St-Benoît."

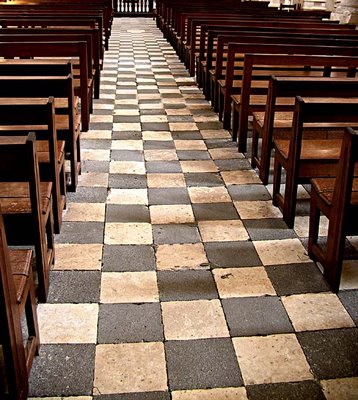

St-Benoît-sur-Loire became a very holy place in Christendom, given Benedict's stature as the founder of the great religious order that carries his name, the Benedictines. The saint's remains, or relics, according to the Michelin guide, were a "source of miracles, of healing, and many wonders that couldn't but draw crowds and spread the fame of the place from then on known as St-Benoît." CHM and I visited the church at St-Benoît on July 15, 2006, and that's when these pictures of the interior of the church were taken. Earlier in the day, we had been at Yèvre, Bellegarde, and Sully, where there are impressive châteaux. We arrived at St-Benoît just ahead of a busload of teenagers in a school group. Restoration work was going on at the church, so parts of the building that we wanted to see were closed to the public. And it was crowded with tourists.

CHM and I visited the church at St-Benoît on July 15, 2006, and that's when these pictures of the interior of the church were taken. Earlier in the day, we had been at Yèvre, Bellegarde, and Sully, where there are impressive châteaux. We arrived at St-Benoît just ahead of a busload of teenagers in a school group. Restoration work was going on at the church, so parts of the building that we wanted to see were closed to the public. And it was crowded with tourists. The great church at St-Benoît stands on the banks of the Loire just a few miles from Sully, in an area called Le Val d'Or — the Valley of Gold. The building that exists today was built mostly around the time of Philippe Ier, in the 11th and 12th centuries. Of the earlier monastic buildings, nothing remains.

The great church at St-Benoît stands on the banks of the Loire just a few miles from Sully, in an area called Le Val d'Or — the Valley of Gold. The building that exists today was built mostly around the time of Philippe Ier, in the 11th and 12th centuries. Of the earlier monastic buildings, nothing remains. The Michelin guide describes the church this way: "A dazzling example of art and spirituality, St-Benoît is enthralling for the simple grandeur of its proportions, the delicate riches of its sculptures, and the soft golden light that seems to drape its vaults and columns." St-Benoît-sur-Loire was a great center of learning and scholarship in the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries.

The Michelin guide describes the church this way: "A dazzling example of art and spirituality, St-Benoît is enthralling for the simple grandeur of its proportions, the delicate riches of its sculptures, and the soft golden light that seems to drape its vaults and columns." St-Benoît-sur-Loire was a great center of learning and scholarship in the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries. The monastery went into decline in the 15th century. The French kings gave it over to hired abbots, some of whom were laymen with no religious mission or education. In the early 16th century, the monks revolted against King François 1er's appointee, and the king had to go in person to St-Benoît with an army to put down the rebellion.

The monastery went into decline in the 15th century. The French kings gave it over to hired abbots, some of whom were laymen with no religious mission or education. In the early 16th century, the monks revolted against King François 1er's appointee, and the king had to go in person to St-Benoît with an army to put down the rebellion. In the second half of the 16th century, during the wars of religion pitting catholics against protestants, one of the abbots of St-Benoît converted to protestantism. He let the protestant forces pillage the monastery and melt down its gold treasures, including the 35-pound reliquary that held St-Benoît's supposed remains. The library was sold off, including some 2000 manuscripts that ended up dispersed all over Europe.

In the second half of the 16th century, during the wars of religion pitting catholics against protestants, one of the abbots of St-Benoît converted to protestantism. He let the protestant forces pillage the monastery and melt down its gold treasures, including the 35-pound reliquary that held St-Benoît's supposed remains. The library was sold off, including some 2000 manuscripts that ended up dispersed all over Europe. You might have noticed the elaborate tile floor upon which Philippe 1er's tomb effigy rests. One source describes it as an Italian mosaic that was completed in 1531. Another calls it a "Byzantine mosaics floor." It is one of the church's extraordinary features.

You might have noticed the elaborate tile floor upon which Philippe 1er's tomb effigy rests. One source describes it as an Italian mosaic that was completed in 1531. Another calls it a "Byzantine mosaics floor." It is one of the church's extraordinary features.